All religious ritual has certain core actions: scriptural recitations, sermons, offerings, or care of icons. Some rites also contain a climactic moment, an essential or culminating point of the entire ceremony. For example, the “Words of Institution” of the Catholic Mass, the “Hriliu” exclamation of Crowley’s rendition, or the Jewish Amidah.

Ancient Egyptian ritual had a number of significant elements. I’ve seen various Egyptologists mention the awakening litany, the “toilet” (of purifying and clothing the statue) and the offerings. The 24-stanza offering litany we use (called “The Ritual of the Royal Ancestors” even though it can be adapted for deities) seems to have been a common element in all temple services; it is the most common, and only consistent, section of temple liturgy that shows up in lay chapels as well.

Yet if Egyptian religious ritual had one culmination, one climax, it would be the revelation and seeing of the icon of the deity, labeled as “seeing the God” (mAA nTr) (1)(2). We see this in all major temples, most famously in the inner sanctum, but also in other chambers. Edfu has several of them, both for public exhibition and private use. In all cases, the Pharaoh or priest lays eyes on the statue of Horus and he proclaims his praises of the God. Sometimes this immediately follows the “revelation of the face” where the shrine box is opened and the statue uncovered for the first time that day. As explained elsewhere, this same theophany of the physical icon is the earthly equivalent of the dawning of the solar disk, which in itself is a daily repetition of the “First Time” - when Horus first arose himself out of latent being and created the universe. (3)

What makes “seeing the God” unique is that it generally occurs at the beginning of the rituals where it occurs, rather than later. The initial entry (or coming out of the palace to go to the temple) and preliminary purifications of the officiant take place first, but then the revelation and/or seeing of the deity closely follow. This makes sense: since almost all the other scenes of various rituals involve praise and offerings before the God, and purification and adorning of the statue, the priest or Pharaoh must reveal the statue of the God to effect these scenes. Rather than building up to a high point like a movie, ancient Egyptian ritual starts off like a roller coaster whose massive drop carries the rest of the ride on its momentum.

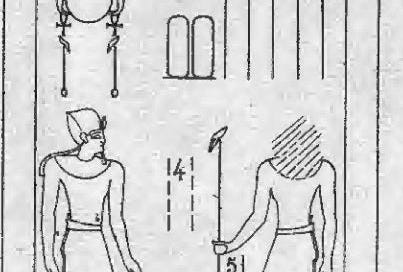

In the Temple of Horus on the Prairie, we like to use the scene of “seeing the God” from the ritual known as the Coronation of the Falcon, from the interior face of the perimeter wall. This Ptolemaic-specific rite had of the temple falcons crowned like a Pharaoh - part of the gradual process of Egyptian society de-emphasizing the role of the earthly king and towards a more idealized symbol of royal authority. It also included invocations to the Goddess Sekhmet for protection during the year. We use this specific scene because one of the Coronation ritual’s other early episodes contains a rather poignant yet brief hymn of praise that encompasses Horus’ solar-creator attributes. This hymn in turn is part of a scene of anointing the statue with scented oil, so it allows for interaction with the icon, a sort of “mini toilet”. The hymn is followed by the Offering Litany from the Hall of Offerings inside the temple which touches on Horus’ heroic aspects vis-a-vis the Eye of Horus mythology. Here is the “seeing the God”/anointing/hymn, with Chassinat notation:

Seeing the God: I enter the Great Throne unhindered, so I can go to the Great Place towards Horus, together with Ra Who Is Horus of the Two Horizons of the Great Throne as His bodily image, with awe of Him entering into and going throughout the limbs. I look upon the strong Falcon in His mysterious form embodied in precious stone: Horus, great in awe. (E VI 58, 4-8)

Anoint statue: The oil of jubilation is upon Your forehead, it makes Your face happy! O lord of the Gods, Your offerings are for You: the galbanum perfume, mixed with styrax, and pure unguent. (E VI 100, 2-4)

Hymn: Hail to You, Ra, who comes in the shape of his ba, Tatenen the primordial mound, who comes as Horus of the Great Throne, the great God, the lord of heaven, falcon of dappled plumage who comes forth from the horizon from the primordial ocean: the illuminator who illuminates this land after He has traversed the sky, for whom the doors of the gateways are opened when He comes forth from the Field of Reeds, who assesses the God’s land, the ruler of Punt who rejoices in the valley of myrrh, the lord of the Gods, the one and only, Kheper-Ra, who makes exist what has come into existence!

May You fly up to heaven, may You traverse the horizon, may You settle on the bank of the sky, may You traverse the earth while You are led properly in Your course, and may You seize the years as the shining one!

Refrain: Fly, fly! Rise, rise! May you fly up, may you fly up!

Your brow is high, when You rise as Horus, lord of the course! Stretch Yourself out! Stretch out Your wings, O living one, ruler of the Ennead. Attack the back of Your enemy as you seize the antelope with Your talons. Your face is bright and Your eyes are made festive, when You repel Your enemies.

Refrain: High, high! Be high! Be exalted! May you reach the sky, may you unite with the horizon, may you open the doors of heaven. (E VI 100, 14 - 101, 7)

I like the above arrangement paired with the Offering Litany because it provides a complete liturgy - seeing the face, praise, statue attention and offerings; cosmic and heroic phases - without being too long, especially for new inquirers. It comes from two specific sources, avoiding a hodgepodge of scenes from various parts of the Edfu temple. This is again in keeping with what we see with lay priests: the offering litanies are by themselves, and an example of the Karnak liturgy in a private home contains just two separate scenes from the main sanctuary rite (revelation of the face and what seems to be a variation of taking off the clothing of the statue). Remember when adapting super-official Egyptian state temple rituals for lay priest use, simplicity and flexibility is both key and historically consistent and liturgically viable.

The hymn and anointing prayer are from the 2017 dissertation The coronation ritual of the falcon at Edfu : tradition and innovation in ancient Egyptian ritual composition, by Carina van den Hoven of Leiden University. This provided the translation of the hymn and anointing, as well as the observation about the falcon replacing the human Pharaoh. I added “the primordial mound” to the name Tatenen, to clarify the definition of one of these many aspects of Horus (taken in turn from Ptah). The refrain labels were also my interjection to facilitate group recitation.

The “seeing of the God” prayer was my own translation, so as usual, caveat emptor. The original hymn includes a mention of Sekhmet, but I used Ra-Horakhty (Ra Who Is Horus On The Two Horizons) instead. This is a valid alteration, since Egyptians would often adapt rituals and simply change the name of the deity invoked (e.g. Amun replaces Amenhotep in a Deir el Medina version of the Offering Litany).

Coppens, Filip (2009) "Temple Festivals of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods", UEE 2009, pg. 2.

Finnestad, Reginhild Bjerre (1985) “Image of the World and Symbol of the Creator”, Otto Harrssowitz, Weisbaden, Germany, pp. 96-101.

Ibid.